EWG presents this exclusive four-part series on Pacific Gas & Electric, or PG&E, the largest utility company in California, with a history of mismanagement and putting profits over consumers. The series shows how PG&E is the poster child for the financial, environmental and policy flaws in energy monopolies, and is a call for for a cheaper, more equitable energy future.

California energy ratepayers could be forgiven for thinking their years-long story of being trapped in PG&E’s flawed power model might not have a happy ending. But the utility has the chance to be a pioneer of clean, equitable energy – if it wants.

Centralized ownership and control of electric system resources, such as solar and battery storage, is key to PG&E’s strategy, not creating a system that is safe, equitable, sustainable and affordable. The company’s emphasis is on a severely overbuilt transmission system and blocking customer ownership of power supply, preferring instead centralized, expensive utility systems.

But the current approach has created a less reliable and dangerous power system in California, which is facing severe climate-related threats, the most prominent being drought and frequent wildfires that cause blackouts and pose severe public health threats.

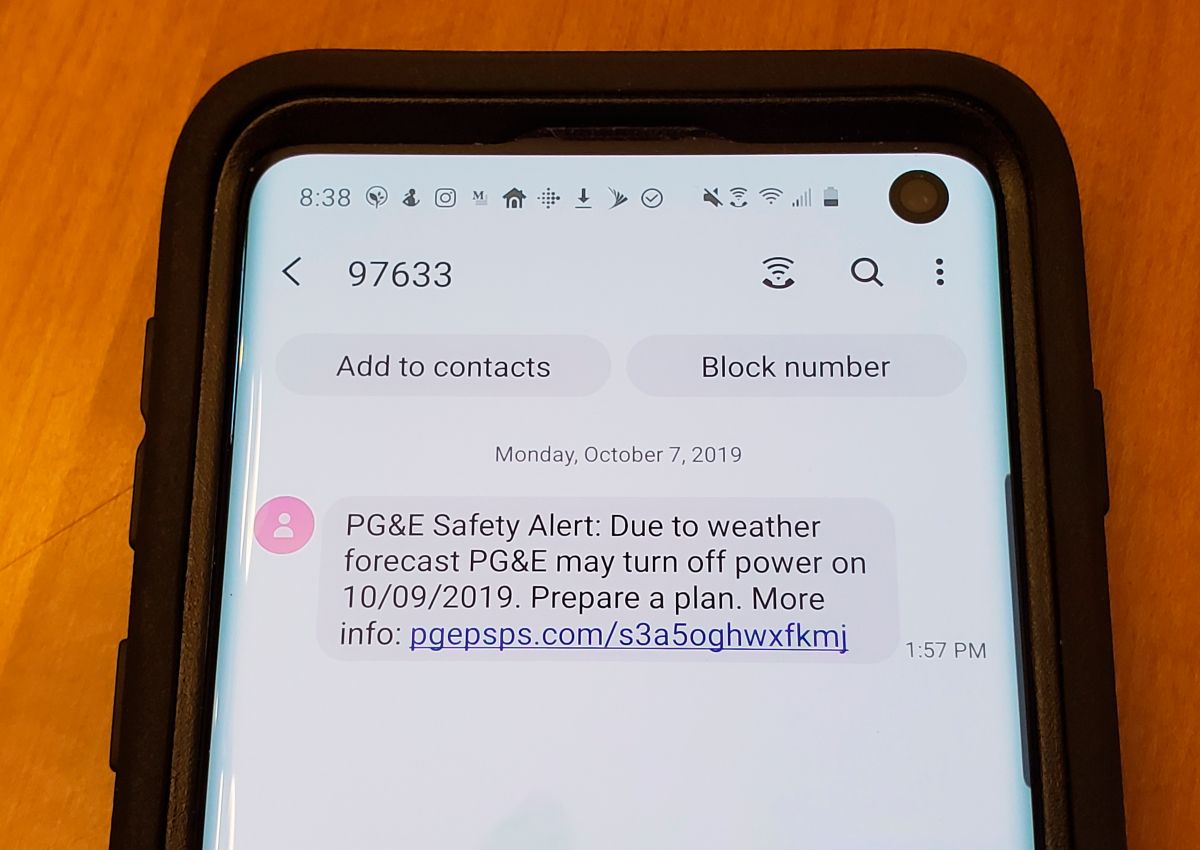

2019 alert to Bay Area residents from PG&E notifying about a potential power shutoff

Photo: Gado Images via Associated Press

What’s needed is a dispersed power system that encourages rooftop solar, embraces clean power sources and aims to make energy something that every California can afford.

PG&E has made some token efforts on this front, outlining a proposal for a remote grid that would reduce reliance on centralized power sources. But the plan is small in scale, it’s not universally available, and it will be slow to implement. And because PG&E has monopoly control on providing power to many Californians, it has no incentive to support public policies or enact company policies that would move the state to prioritize a customer-centric, decentralized electric system that strategically mitigate climate impacts on the electric system.

EWG’s alternative model could finally break PG&E’s stranglehold on ratepayers, make a serious step forward in tackling the climate emergency, and slash power bills across the state.

Stockholders, not ratepayers, should be responsible for PG&E’s wildfire liabilities.

We don’t have all the solutions to PG&E’s years-long problems. But why do Californians have to accept the status quo? Is it so hard for policymakers and others to muster the energy and motivation needed to finally tackle the problems with the utility?

The only thing standing in the way is a lack of leadership to make a firm stand against PG&E’s flawed way of doing business and launching an eye-catching energy transformation.

Equitable energy: Overdue in California

EWG’s approach would finally hold PG&E, not ratepayers, accountable for unnecessary investment decisions that exacerbate an overbuilt electric system. And it would make PG&E own its negligence, which has caused wildfires that threaten public health, and compromised quality of life in the state. The key elements of the model are:

- Impose a more robust regulatory regime over infrastructure investment

The current monopoly business model encourages utilities to overbuild power line infrastructure and power plants to pad profits. EWG would place these decisions under strict regulatory control. From utility planning to individual filings, utilities would have to prove the projects are necessary and that cheaper alternatives do not exist.

- Prioritize least-cost planning, shifting investment to distributed electric grid

Utilities prefer utility-scale approaches to providing service, so they can preserve the centralized electric system model. But distributed, decentralized systems are more resilient and less expensive than a system weighted to monopoly-controlled centralization of assets.

Rooftop solar and storage in buildings and microgrids are considered distributed resources, as are energy efficiency technologies and measures to reduce electric use. These cheap energy resources can help reduce electric demand as California moves to electrify buildings, phasing out natural gas use. And batteries in electric vehicles can be used to help maintain electric system reliability, if their use is properly coordinated on the distribution system.

Under the EWG rubric, utilities would have to prove distributed resources are more expensive or unavailable before building utility-scale infrastructure and power plants. Regulators would have to assess not only costs but also resiliency, affirming that distributed resources are better for avoiding blackouts, and maintaining service when they do occur.

EWG also proposes that electric systems are cheaper when utilities own less of them, as with a decentralized grid. PG&E could still make money under our model, and investments in the resources and labor to produce the distribution system will still be needed.

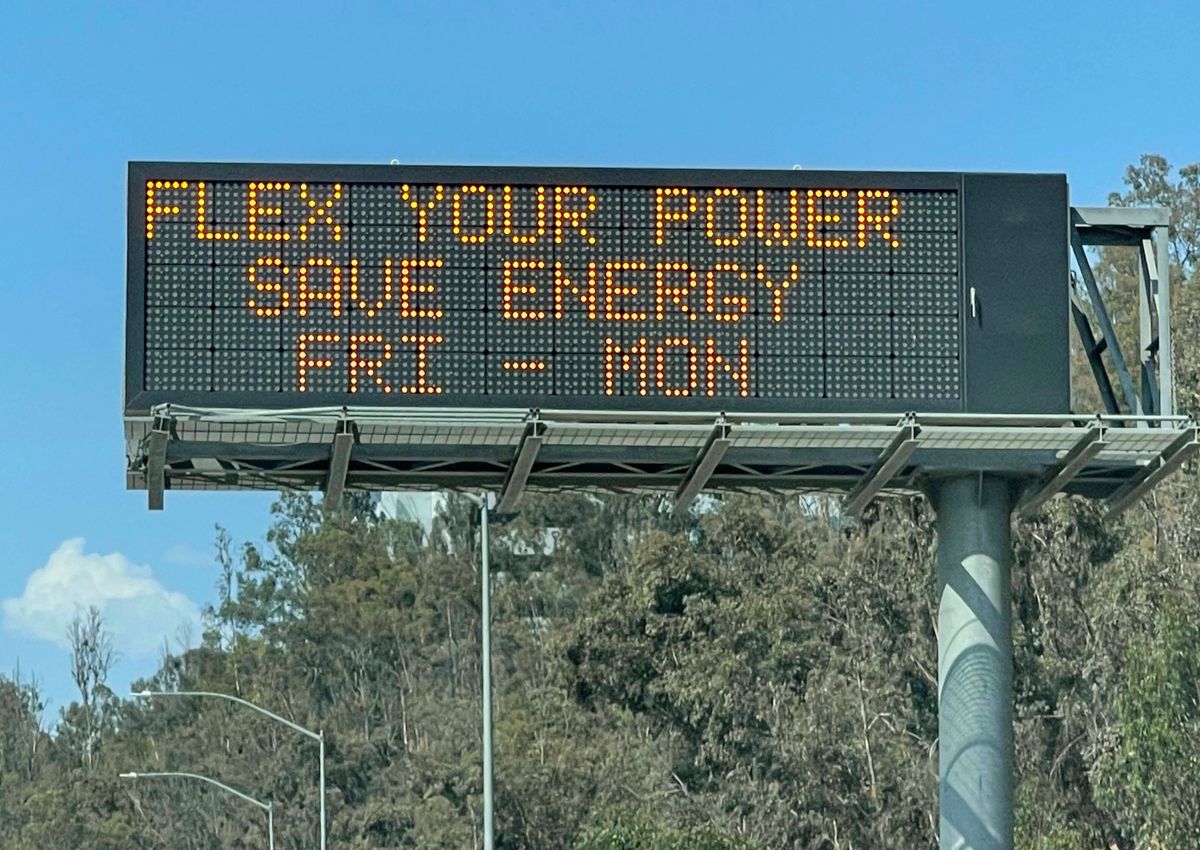

2021 CalTrans sign in Monterey Park, Calif., calling for people to flex their power during the week

Photo: Kirby Lee via Shutterstock

- Provide clean energy access for working-class customers and communities of color

Critical to success of the distributed energy system, energy equity and electric bill affordability is providing working-class customers and communities of color with access to these money savings technologies. The EWG model encourages state and municipal programs to deploy clean energy in such areas, but it’s vital that there be no fees attached. Affordable solar and other clean power are a false promise when they come with a huge bill.

Microgrid policy would also be changed to eliminate the state’s “over the fence line” rule, which prohibits microgrids from expanding beyond a single property.

- Eliminate pricing structures that sustain the flawed grid and hinder clean energy

Ratemaking isn’t perfect, but PG&E’s claim that solar customers are reaping payments from the utility for power generated on their properties and shifting costs to non-solar ratepayers isn’t true. Utilities will always argue that customers who use the least amount of power are subsidized by those who use more,1 and that’s how PG&E justifies significant fixed fees.

But high fixed charges raise bills for low-use customers while slashing them for high-use customers.2 But contrary to utility claims, those who use the least amount of power exact less stress, or demand, on the system and therefore should pay less. This is known as cost causation – those using more energy pay more; those using less energy pay less.3 4

An affordable, least-cost system is possible only with the proper price signals, which means that customers need to be able to control their bills. For residential customers, most utility costs are recovered through their use of energy – being charged by the kilowatt-hour, which can be reduced through efficiency, solar and storage investments. High fixed charges impose fees for the privilege of being a customer before any energy is used. They discourage clean energy.5

High fixed charges do send price signals, as utilities claim, but they send the wrong ones. The result is an unaffordable, overbuilt and overly expensive electric system.

EWG’s model envisions no fixed charge other than the traditional charge based on the number of customers covering billing, direct connection to the power system and collection costs,6 which historically has been around $10 per month. All other charges for residential customers should be levied according to the amount of electricity a household uses per month.

EWG’s model demands that utility investments provide customer benefits – that they not just exist as a way to pad profits. In decisions about transmission, distribution or power plant additions, utilities would have to prove that their proposals are the lowest-cost option and provide the most resiliency against climate change, supporting distributed resources that allow customers and the economy at large to maintain service during fire season and other disruptions. The state legislature should write laws to steer regulator and utility decision-making in that direction.

- Prevent utilities from shifting costs and liabilities to ratepayers

Local investments in energy efficiency, solar and storage can eliminate billions in transmission and distribution costs. But what if a utility builds an unneeded power plant or transmission line? These are stranded assets, and PG&E argues ratepayers should pay for those flawed projects.

Utilities are well aware of the energy market, the costs of energy technologies, improvements, how investor dollars are flowing, and expected developments into the future as well as the growing investor interest in reducing climate risks. PG&E continues to make specious arguments for excessive transmission investment and against policies that support customer-owned solar. This flies in the face of market developments and sensible spending decisions.

Given how quickly technology changes, with continuous improvements in solar, storage and energy efficiency, it is also incumbent on regulators to assess utility investments,based in part on these market developments. If assets become stranded before the useful end of their lives, we can assume the utility knew that would happen, and ratepayers shouldn’t be forced to bail it out.

Under EWG’s utility business model, utility stockholders would be responsible for all possible costs of stranded assets, within legal parameters established by the Supreme Court,7 not ratepayers. Along with eliminating high fixed charges and creating a more rigorous regulatory regime, California could finally instill in PG&E and other utilities more financial discipline.

And stockholders, not ratepayers, should be responsible for PG&E’s wildfire liabilities. To allow the company to convert this kind of negligence and reckless endangerment into a profit center is unconscionable. EWG’s model would prohibit such a result by prohibiting recovery of those costs from ratepayers. In 2019, Gov. Gavin Newsom suggested that all options were on the table in light of PG&E’s poor management record, including converting PG&E to a publicly operated utility.8 This may be the best course of action.

Melted child play-set in the aftermath of 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, Calif.

Photo: Tina Lawhon via Shutterstock

Learning from PG&E’s flawed past

EWG has suggested that the best ownership structure for dealing with California wildfires, affordability and a coherent state policy may be converting PG&E into a publicly run utility, as originally envisioned in the Golden State Energy Act. Instead, that became a way for PG&E to save tens of billions in wildfire liability.9

Policy changes can be hard and unpredictable, but it’s beyond time for California ratepayers to have a fair, affordable power system that advances clean energy and combats the climate emergency.

3 https://www.icc.illinois.gov/docket/P2014-0224/documents/224001

4 Specifically, in a 2015 rate case, in which utilities were asking for a high fixed charge, the Illinois Commerce Commission stated, “The Companies also offer the false hope of encouraging conservation through their proposed rate design. Ms. Egelhoff (a utility witness) claimed that customers’ incentives to conserve are provided through required energy efficiency programming and that incorporating conservation into rate design is improper because it is ‘contrary to cost causation principles.’ PGL-NS Ex.43.0 at 7. However, the Companies’ proposal violates cost causation principles by failing to ‘properly recognize that customers with different demands impose differing costs on the system.’ Staff Ex. 9.0 at 5.” (emphasis added)

6 https://www.raponline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/appendix-d-smart-rate-design-2015-aug-31.pdf

7 See Duquesne Light Co. v. Barasch, 488 U.S. 299 (1989) https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/488/299/