Trouble in Farm Country: Ag Runoff Fouls Tap Water Across Rural America

Jump To

August 2017

By Craig Cox, Senior Vice President for Agriculture and Natural Resources

The 672 residents of Pretty Prairie, Kan., are surrounded by cropland – more than 12,000 acres of winter wheat, corn, soybeans and sorghum within a four-mile radius of the Farmer's Co-op grain elevator. Each year, those crops are sprayed with hundreds of thousands of pounds of fertilizer – the main cause of pollution in the town’s tap water, which has one of the nation's highest levels of a chemical suspected to cause cancer.

The problem is nitrate, a chemical that comes from commercial fertilizer and manure. For more than 20 years, the level of nitrate in Pretty Prairie’s tap water has exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency’s legal limit. In 2014 and 2015 the level was twice the legal limit.

The limit – 10 parts per million, or ppm – was set in 1962 to protect against blue baby syndrome, a potentially fatal condition that starves infants of oxygen if they ingest too much nitrate. But up-to-date science indicates that's not the only concern, and that the legal limit is at least twice too lax.

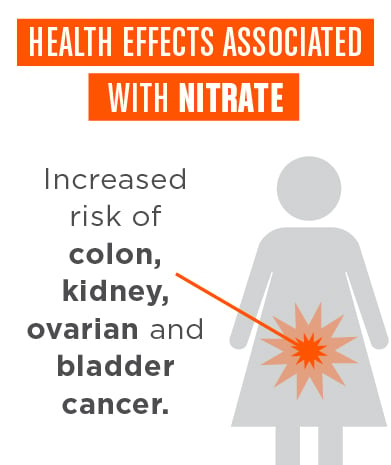

Studies by the National Cancer Institute have found that drinking water with just 5 ppm of nitrate increases the risk of colon, kidney, ovarian and bladder cancers. In Pretty Prairie, parents with infants under 6 months old, and nursing or pregnant women can get free bottled water, but that does nothing to protect other residents from cancers that may not show up for years or decades.

Nitrate pollution, which can also come from septic systems, afflicts towns and cities in farm country across the U.S. And it's just one of the threats industrial agriculture poses to tap water:

- Fertilizer and manure also contain phosphorus, which can trigger massive blooms of algae in lakes and other drinking water sources. A type of algae called cyanobacteria produce toxins that can end up in drinking water.

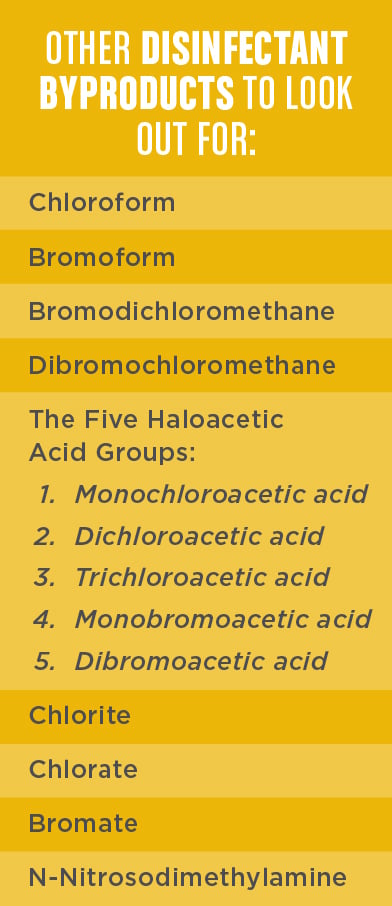

- When utilities treat water with chlorine to remove algae, fecal bacteria and other farm pollutants, it creates chemical byproducts called trihalomethanes, or TTHMs, linked to cancer and reproductive harm.

- Federal policies do little to keep farm pollution from getting into tap water in the first place. The expensive treatment needed to remove these contaminants can bankrupt small rural communities.

In recent years, much attention has been given to urban drinking water problems. But EWG’s Tap Water Database, which collects results of tests for contaminants by nearly 50,000 utilities nationwide, shows that rural Americans are bearing the brunt of the health risks and economic costs of unchecked farm pollution.

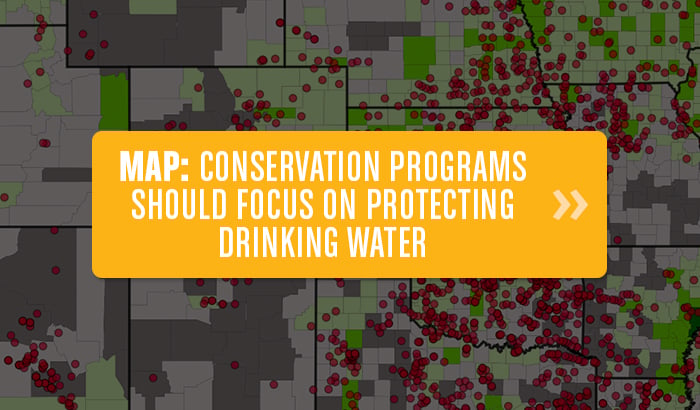

Pretty Prairie is in Reno County, where eight other small towns have nitrate levels at or above the increased cancer risk level of 5 ppm. Nationwide, 97 percent of public drinking water systems with nitrate at or above that level serve 25,000 people or less.

Just like Pretty Prairie, those 1,683 communities are surrounded by millions of acres of cropland on which nitrogen-rich fertilizers and manure are applied every year. In 2014 and 2015, average nitrate contamination in 463 of these communities was at or above 7.5 ppm, well above the level of nitrate that National Cancer Institute studies say increases the risk of cancer, and 118 had contamination at or above the EPA’s legal limit.

Rural Americans are bearing the brunt of the health risks and economic costs of unchecked farm pollution.

Two-thirds of communities with nitrate levels at or above 5 ppm are in 10 states where agriculture is big business.1 Almost three-fourths of communities whose drinking water is at or above the legal limit are found in just five states – Arizona, California, Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas. Even a cursory look at the map above shows that these communities are clustered in some of the most heavily farmed counties in the nation.

The millions of rural Americans who get drinking water from their own wells may be at even greater risk. Between 1991 and 2004, the U.S. Geological Survey tested private domestic wells for nitrate. In areas dominated by agriculture, at least 7 percent of the wells tested exceeded the legal limit for nitrate. One-fourth of shallow wells under intensively farmed land were contaminated above the legal limit.

Cost of removing nitrate can be crippling

Eighty-five percent or more of the communities with elevated levels of nitrate have no treatment systems in place to remove the contaminant.

Last year, the EPA ordered Pretty Prairie to build a new water treatment system to lower nitrate levels. The system could cost $2.4 million – well over $3,000 for every person in town. Eighty-five percent or more of the communities with elevated levels of nitrate have no treatment systems in place to remove the contaminant. Like Pretty Prairie, many have longstanding contamination problems, but have balked at the high cost of treatment.

Ion exchange and reverse osmosis systems are the most common technologies used to get nitrate out of drinking water. Ion exchange systems pass water through a resin to remove nitrate. In a reverse osmosis system, pressurized water is pushed through a membrane that removes nitrate and other contaminants.

Treatment costs will vary for each utility and contamination problem. But a range of costs cited in a 2012 report from the Center for Watershed Sciences at the University of California at Davis can be used to make rough estimates. A community of just under 5,000 people could incur annual costs ranging from $195,000 to $1.1 million to build and operate an ion exchange system. A reverse osmosis system would be even more expensive, ranging from $1.1 million to $4 million a year.

Nitrate is just tip of the iceberg

When it rains, the runoff from poorly protected farm fields carries not only nitrogen, but phosphorous and organic matter like manure, mud and crop residues into streams. Phosphorous from fertilizer triggers blooms of algae, which multiply the amount of organic matter in the stream.

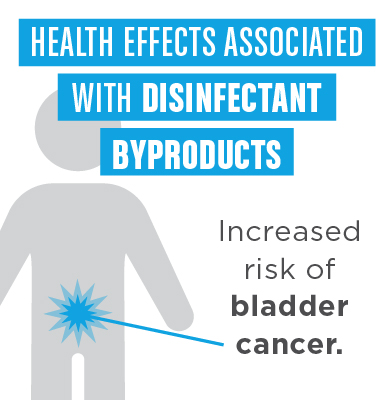

This puts water utilities in a bind. Drinking water contaminated with fecal bacteria or pathogens makes people sick and can lead to potentially fatal diseases such as dysentery and cholera. To protect people in the short term, utilities must disinfect the water with chlorine or other chemicals. But those chemicals react with algae and other organic matter in the water to produce other chemicals with long-term health hazards – disinfection byproducts called trihalomethanes, or TTHMs.

Drinking tap water contaminated with TTHMs increases the risk of developing bladder cancer in humans. In animal studies, TTHMs are also associated with liver, kidney and intestinal tumors. Studies suggest that TTHMs increase the risk of problems during pregnancy as well, including miscarriage, cardiovascular defects, neural tube defects and low birth weight.

The EPA has set a legal limit of 80 ppb for TTHMs in drinking water. The limit was based on the technical feasibility of removing TTHMs from drinking water after disinfection and did not consider their long-term toxicity. In 2010, California state scientists estimated that exposure to 0.8 ppm of TTHMs – 100 times lower than the federal legal limit – would pose a one-in-a-million lifetime risk of cancer.

Most communities with high levels of TTHMs in tap water rely on surface water supplies that are more vulnerable to polluted runoff from farm fields. The Tap Water Database shows that water supplies in 1,647 communities, serving 4.4 million people, are contaminated with TTHMs in amounts at least 75 times higher than California’s one-in-a-million cancer risk level. Between 2014 and 2015, 411 of those communities had TTHMs at or above the EPA’s legal limit.

As with nitrates, high levels of TTHM contamination are concentrated in major farming states. About 56 percent of communities with TTHM levels between 60 ppb and the legal limit of 80 ppb are in 10 states.2 Five states – California, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma and Texas – cover almost two-thirds of communities with TTHM contamination above the legal limit. Three of those states are also in the top 10 nationwide for high nitrate contamination.

Prevention is the key to keeping TTHMs and other toxic disinfection byproducts out of drinking water. Getting TTHMs out of drinking water once they have formed can be complicated and expensive. Also, disinfection is commonly the last step in water treatment, which makes it even more harder to remove TTHMs once they have formed. Different disinfection processes can decrease TTHM levels, yet produce other, similarly toxic byproducts, and even increase the leaching of lead from pipes.

Utilities can use enhanced coagulation, granular activated carbon or nanofiltration to remove algae and other sources of organic matter out of the water before it is disinfected. In the Tap Water Database, EWG only has data about existing treatment systems for a little more than half of the small communities with high levels of TTHMs. But of those for which we have information, only about one in eight have treatment systems specifically for TTHMs and other disinfection byproducts.

Act now before it’s too late

For Pretty Prairie and other communities with extremely high contamination levels, it may be too late to stave off the problem. Expensive new treatment facilities may be the only option because these water supplies are just too polluted.

But more than 80 percent of communities with elevated nitrate levels are still below 75 percent of the legal limit. Aggressive action now to cut pollution and clean up the rivers, streams and aquifers that rural Americans depend on for drinking water could protect families and avoid potentially crippling costs. Simple and familiar conservation practices, if applied in the right places, can often improve water quality dramatically.

The Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, for example, identified three conservation practices that are highly effective in keeping nitrate out of water supplies. At the top of the list is keeping fields covered with grasses, or cover crops, after the commercial crop is harvested. Practices that improve the fertilizer management, and that cut erosion and runoff from fields, are also effective ways to reduce nitrate pollution and keep TTHMs out of drinking water.

States and counties could and should act on their own. But the upcoming federal farm bill is a remarkable opportunity to help local communities secure clean and safe drinking water by keeping nitrates and other contaminants out of the water in the first place.

Need to focus conservation practices

Clearly, there is a huge opportunity to focus these federal programs more tightly to head off the kind of crisis facing Pretty Prairie.

Federal farm programs pay farmers to adopt conservation practices that help keep tap water clean. EWG’s Conservation Database provides the first-ever detailed look at what practices farmers are being paid to adopt in every county nationwide. The data reveal a stunning under-investment in the practices needed to protect drinking water in the places where it is most threatened.

For example, almost 40 percent of the communities contaminated with nitrate above 5 ppm are in counties where none of the contracts in the federal Conservation Stewardship Program, or CSP, paid for the planting of cover crops. Almost half of those communities are in counties where no CSP contracts pay farmers to implement practices to curb erosion and runoff, and almost a third are in counties where none of the CSP contracts help farmers improve fertilizer management.

The federal Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP, follows the same pattern. Almost 40 percent of communities with elevated nitrate levels are in counties where none of the EQIP contracts support the planting of cover crops. Almost a third are in counties with no EQIP support for erosion and runoff control practices, and more than a third are in counties with no EQIP support for managing use of nitrogen and phosphorous fertilizers.

Looking at communities with nitrate above the legal limit, there is an even more pronounced lack of support to farmers to implement pollution prevention practices through CSP and EQIP. Clearly, there is a huge opportunity to focus these federal programs more tightly to head off the kind of crisis facing Pretty Prairie. Instead, it seems we are relying almost solely on treatment to clean up drinking water rather than keeping contaminants out of the water in the first place.

Voluntary programs aren’t enough

Farm bill conservation programs need more money and can play an important role. But we can’t buy our way to clean drinking water for rural communities.

It is not fair to ask taxpayers to pay for everything farmers should do to be good neighbors, and there’s not enough tax money available anyway. What’s more, if farmers voluntarily implement a conservation practice, they can also voluntarily stop using that practice. As a result, conservation practices come and go, and we end up spinning our wheels while spending billions.

But it is more than fair to expect farmers and landowners to expand their efforts to protect the environment in return for the generous farm and insurance subsidies they receive. According to the Congressional Budget Office, in 2016 alone, those subsidies totaled $14.5 billion, with projections of another $64.3 billion over the next five years.

Strengthen the conservation compact

The conservation compact between farmers and taxpayers in the 1985 Farm Bill sparked dramatic progress in cutting runoff from the most vulnerable cropland and saving wetlands. Now it’s time to require all subsidized growers and all the cropland they farm to meet common-sense, easily implemented conservation standards to cut polluted runoff. It’s also past time for the Department of Agriculture to ensure that those requirements are met.

A new and stronger conservation compact will be a fairer deal for taxpayers, level the playing field for conservation-minded farmers and build a foundation on which a more effective conservation title can be built.

The 2018 Farm Bill conservation compact must include a quid pro quo: To remain eligible for farm program benefits and crop insurance premium subsidies, farmers and landowners plan and fully apply an approved conservation system on all annually tilled cropland.

The compact must also ensure that the conservation system:

- Achieves a rate of soil erosion no greater than the soil loss tolerance level on all annually planted cropland.

- Prevents ephemeral gully erosion.

- Establishes and maintains a minimum of 50 feet of perennial vegetation between annually tilled cropland and intermittent or perennial waterways.

Farmers and landowners should also be required to have an approved conservation system plan within five years of the farm bill's enactment and to fully apply the approved system within 10 years of enactment.

Congress should also set aside up to $300 million annually – just 0.02 percent of the funding for farm and crop insurance subsidies – to fund technical assistance, status reviews and other tasks needed to fully implement the new compact. The USDA should be required to annually review compliance status on no less than 5 percent of the tracts subject to the quid pro quo.

Wicitra Mahotama, Agriculture Conservation and Environment Analyst; Soren Rundquist, Director of Spatial Analysis; and Anne Weir Schechinger, Senior Analyst, Economics, also contributed to this report.

1 Arizona, California, Illinois, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin and Texas.

2 California, Florida, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma and Texas.