Industrial facilities across the country could be unwittingly burning the Pentagon’s legacy firefighting foam, according to an analysis of Pentagon records. The firefighting foam is made with the toxic “forever chemicals” known as PFAS.

And the incineration could be posing health risks to tens of thousands of people by exposing them to harmful PFAS emissions and contaminated drinking water. Most affected are communities living near or downwind of these facilities, who are already plagued by the toxic chemicals in their environment.

In a rush to destroy its stockpiles of PFAS-based firefighting foam, the Department of Defense has recently exploited a loophole that allows it to dispose of its PFAS waste through a process called fuel blending.

According to a Bennington College analysis, the DOD sent large amounts of its stockpiled foam to fuel blending facilities between 2016 and 2020, where it was mixed with other hazardous wastes and commercial fuel, then sent to be used as fuel at certain industrial furnaces, incinerators and cement kilns across the country.

Congressional leaders are advancing legislation to address the DOD’s use of incineration to dispose of PFAS waste, including through the use of fuel blending, to ensure that the DOD can no longer exploit this loophole.

DOD has known since the 1970s that the foam was toxic. Very low doses of PFAS chemicals in drinking water have been linked to suppression of the immune system and are associated with an elevated risk of cancer, increased cholesterol and reproductive and developmental harms, among other serious health concerns.

PFAS are called forever chemicals because they build up in our bodies and never break down in the environment.

Decades of danger: DOD’s stockpiles of PFAS firefighting foam

For more than 50 years, DOD has required the use of the PFAS-based firefighting foam known as aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF. It has been widely used for decades, largely for training purposes at military installations.

As a result, at least 385 military sites have confirmed PFAS contamination of their drinking water supplies, and nearly 300 installations have suspected pollution, according to Pentagon records obtained by EWG.

Chemical companies eventually phased out two of the oldest and most notorious PFAS chemicals – PFOS, once an ingredient in 3M’s Scotchgard, and PFOA, formerly used to make DuPont’s Teflon. The military then shifted to newer formulations of AFFF, made with “short chain” PFAS.

Evidence suggests these chemicals pose many of the same health risks.

But this change left DOD with large stockpiles of older formulations in need of disposal or destruction, which it did most often through incineration or burning. According to Pentagon records, since 2016, the military has entered into contracts to incinerate more than 20 million pounds of AFFF.

Health and environmental risks of burning PFAS waste

The very qualities that make PFAS-based AFFF well suited for extinguishing jet fuel fires also make it difficult to destroy. There is no evidence that PFAS completely break down under typical industrial incineration practices.

In fact, studies show incinerators likely do not completely destroy PFAS, and they emit PFAS and toxic chemical byproducts. Research shows PFAS emitted through facility air stacks can travel several miles downwind.

EWG scientists have warned that attempts to destroy PFAS through incineration could pollute frontline communities near or downwind of these facilities. The process can further cycle PFAS contamination back into these areas and the environment when PFAS are deposited in soil and drinking water supplies in downwind communities, increasing their exposure.

Researchers from Bennington College, in Vermont, found elevated levels of PFAS in soil and water samples taken from neighborhoods near the Norlite incinerator in Cohoes, N.Y., which received AFFF from the DOD until 2020. Communities in Ohio and West Virginia have raised similar concerns about the Heritage incinerator, in East Liverpool, Ohio, which also has a contract with the DOD to incinerate AFFF.

Some studies suggest, under ideal conditions, PFAS may break down if incinerated at facilities that can reach and maintain extremely high temperatures, more than 1,000 degrees Celsius. But the EPA admits “the effectiveness of incineration to destroy PFAS . . . is not well understood.”

Even DOD grasps that not enough is known about the combustion of PFAS-based firefighting foam. In April 2017, the Air Force requested proposals for the study of its disposal because “no satisfactory disposal method” had been identified.

Widespread concerns about PFAS loophole pollution

Why has PFAS-laden firefighting foam made the detour to fuel blending facilities in the first place?

It’s not entirely clear. Pentagon records of AFFF shipments stop once the foam reaches a fuel blending facility. EWG analysis of records submitted to Environmental Protection Agency’s online hazardous waste database show that shipments of AFFF often change hands multiple times, making it nearly impossible to follow individual shipments of AFFF from cradle to grave.

Analysis of Pentagon records led by David Bond, Ph.D., a professor at Bennington College, tracked DOD’s firefighting-foam stockpile. The records were obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request and a New York state public records request.

Bond’s analysis found up to a quarter of the PFAS-based foam – roughly 5.7 million pounds from 2016 to 2020 – was sent to fuel blending facilities instead of directly to incinerators.

Of that, about 3.2 million pounds of AFFF ended up at fuel blending facilities that have permits for blending fuels, including hazardous waste. But another 2.5 million pounds of AFFF ended up at facilities that advertise themselves as fuel blending facilities but don't have EPA permits for fuel blending.

This raises the question whether AFFF is being blended into fuel that would not be considered as hazardous waste or those facilities are storing AFFF and transferring it to other fuel blending facilities. If AFFF is being blended into fuel not considered hazardous waste, where is that fuel being burned?

PFAS chemicals are not currently classified as “hazardous waste” under our federal waste disposal laws. That means that historically DOD, not EPA, has been able to decide whether legacy AFFF should be treated as hazardous waste.

Hazardous wastes and fuels blended with hazardous waste can go only to facilities with certain permits. But if a contract for disposal does not stipulate that AFFF must be sent to a hazardous waste facility or if the AFFF is blended with fuels that do not contain other hazardous wastes, there are few federal restrictions on where facilities can send the blended fuel.

Some hazardous materials blended at these facilities, like flammable solvents, paints and coatings and petroleum products, are combustible. It makes sense that companies could justify disposing of them through fuel blending, though there may be other public health reasons to be concerned about them.

But AFFF serves no functional purpose in blended fuel. In fact, by every measure the PFAS chemicals in AFFF could make blended fuels less combustible and may be impossible to destroy even under the best conditions.

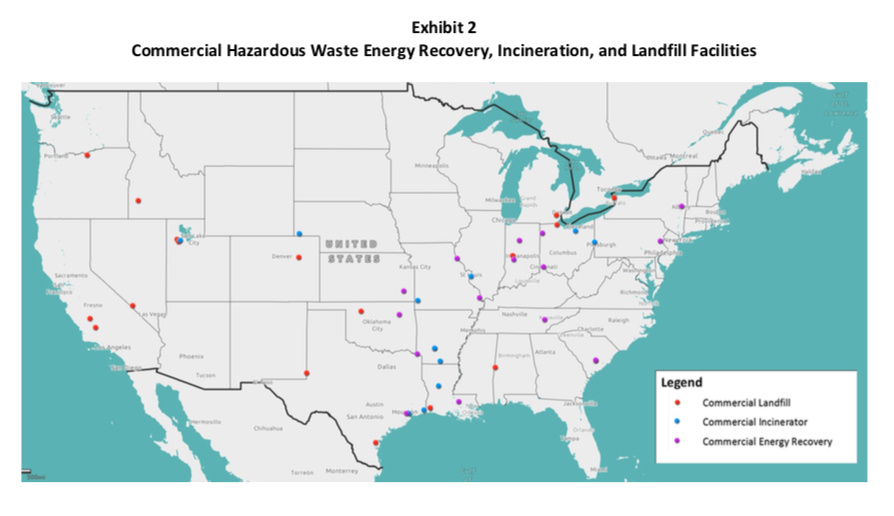

According to an EPA report, there are about two dozen facilities in Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Utah that can receive blended fuels containing hazardous waste.

Source: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Capacity Assessment Report Pursuant to CERCLA Section 104(c)(9) (December 17, 2019)

However, hundreds if not thousands of industrial furnaces and boilers across the country could receive blended fuel not considered hazardous waste, raising the question: Could any of those facilities be receiving fuel blended with AFFF for use in their operation? If so, are they aware that the fuel they are receiving contains PFAS?

Petrochemical companies, as well as states like Rhode Island and Massachusetts, have also sent old PFAS-based firefighting foam to fuel blenders, where it ultimately is sent to facilities that burn waste for energy generation.

The DOD’s reliance on fuel blending is almost certainly just a way to quickly dispose of its stockpiled PFAS waste – a growing source of liability.

What’s more, the lack of transparency means that it’s not just the industrial facilities that could be burning PFAS-contaminated blended fuel that are in the dark about whether they’re being exposed to harmful PFAS emissions.

The public is, too. And they deserve to know whether, and to what extent, the DOD is still exploiting this loophole.

Congress and localities move to tackle the problem

Concern has grown over DOD’s incineration of AFFF at facilities like Norlite and Heritage. In response, in 2019, Congress included a provision, known as Section 330, in the National Defense Authorization Act, or NDAA, for Fiscal Year 2020 targeting the incineration of PFAS materials.

The provision required that any incineration of PFAS by the Pentagon, including burning of legacy firefighting foam, adhere to the requirements of the Clean Air Act and at a temperature adequate to break down PFAS chemicals.

The provision also required DOD to lower PFAS emissions as much as it could, including eliminating them, if possible.

A separate provision in the same law, Section 7361, required the EPA to provide guidance on the disposal and destruction of PFAS, including in firefighting foam.

In February 2020, Earthjustice, along with the Sierra Club and frontline communities, filed a lawsuit in federal district court challenging DOD’s contracts to incinerate AFFF. The group claimed the incineration was not following the requirements of Section 330.

Defying the congressional mandate, the Pentagon responded that the directions in the FY 2020 defense law didn’t apply to AFFF incineration contracts entered into before the law was enacted.

This prompted the city of Cohoes to temporarily halt PFAS incineration at the Norlite facility. Later in the year, New York enacted a law banning incineration of PFAS at similar facilities.

The Norlite facility is no longer accepting shipments of legacy AFFF for incineration, so DOD may have been more likely to ship more of its legacy foam to fuel blending facilities. Although the DOD has terminated its contract with at least one fuel blending facility, researchers at Bennington have identified other fuel blending facilities that have received DOD PFAS waste.

Hope on the horizon: Congress poised to tackle PFAS again

As public health and environmental concerns mount regarding the use of incineration as a method of disposal for PFAS, lawmakers are pushing for more safety measures.

Adam Smith (D-Wash.), chair of the House of Representatives Armed Services Committee, included a provision in the FY 2022 NDAA to temporarily stop DOD’s unsafe incineration of legacy foam and other PFAS waste.

Rep. Andy Levin (D-Mich.) successfully offered an amendment with Reps. Elissa Slotkin (D-Mich.), John Sarbanes (D-Md.), Antonio Delgado (D-N.Y.), Brian Fitzpatrick (R-Pa.), Teresa Leger Fernández (D-N.M.), Deborah Ross (D-N.C.), Nancy Mace (R-S.C.) and Bill Posey (R-Fla.) to build on the provision and ensure the moratorium apply to AFFF sent to fuel blending facilities, among other things.

Sen. Jean Shaheen (D-N.H.) has offered a similar amendment to the Senate version of the NDAA for FY 2022, which is expected to be voted on this week.

For the sake of all frontline communities, the Senate must halt DOD’s unsafe incineration of PFAS and close the fuel blending loophole by adopting the House-passed provision.