Executive summary

Every time they drink a glass of tap water, people in the mid-Ohio River Valley of West Virginia and Ohio may be consuming unsafe amounts of an industrial chemical linked to cancer, birth defects, heart disease and other illness. More than a decade after this threat became known, government regulators have failed to set enforceable standards to ensure the water is safe – and now, new science says the danger may be much greater than either residents or regulators thought.

In 2005, DuPont settled a class-action lawsuit brought on behalf of 70,000 mid-Ohio Valley residents for decades of fouling their drinking water with a highly toxic chemical once used to make Teflon. As part of the settlement, DuPont1 is paying for technology to filter – but not eliminate – the toxin from six area water systems.

Next month, the first of approximately 3,500 personal injury lawsuits2 from mid-Ohio Valley residents who got sick from drinking the contaminated water will go to trial. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has spent a decade studying the health hazards of the Teflon chemical, known as PFOA,3 but may take another four to six years before even deciding whether to set a legally enforceable maximum pollution level for drinking water. In 2009, EPA set a non-enforceable Provisional Health Advisory level – a temporary, voluntary standard to help utilities and health officials decide when to take action to reduce peoples’ exposure – but the agency didn’t follow up with a rule that carries the force of law. That advisory level remains the only federal guidance on how much PFOA is safe in drinking water.

Now two leading environmental health scientists have published research with alarming implications: PFOA contamination of drinking water is a much more serious threat to health, both in the mid-Ohio Valley and nationwide, than previously thought. Their research finds that even very tiny concentrations of PFOA – below the reporting limit required by EPA’s tests of public water supplies – are harmful. This means that EPA’s health advisory level is hundreds or thousands of times too weak to fully protect human health with an adequate margin of safety. The implications:

- The settlement set a “trigger level” of PFOA to determine which West Virginia and Ohio water systems DuPont would pay to have filtered. That trigger level is more than 160 times the amount the new research says is safe. Filtration has cut PFOA to almost non-detectable levels in many of the water systems covered by the settlement, but even the least contamination measured exceeds the amount the new research says is safe.

- Only those people in the mid-Ohio Valley who became sick after drinking water at or above that trigger level are eligible to be plaintiffs in the upcoming trials, but the new science indicates that many more people who drank less heavily contaminated water could also have been harmed. (They may file suits in the future, but will not have the benefit of the extraordinary concession DuPont has made for the upcoming trials – that PFOA at the trigger level can cause certain diseases.)

- Two water systems in the region – Parkersburg and Vienna, W. Va. – were not covered by the 2005 settlement because their PFOA contamination at that time was just under the trigger level. Without benefit of the state-of-the art filtration technology installed in other systems, water samples taken in Vienna in May 2007 had PFOA levels more than 180 times higher than the new research says is safe,4 and those taken in Parkersburg last September were more than 130 times the new safe level.

- Since 2013, an EPA testing program has found PFOA in 94 public water systems in 27 states. These systems provide drinking water to more than 6.5 million people. The vast majority of water samples tested had no detectable level of PFOA, and in every system with PFOA the level was well below the EPA advisory level. But among the samples with PFOA, statewide average levels ranged between five times and 175 times the level described by the new research as safe5.

- To replace the provisional health advisory limit set in 2009, EPA officials are in the process of establishing a long-term health advisory level for PFOA in drinking water. A draft EPA study released last year suggested that the advisory level being considered could be more than 300 times the new safe limit. Whatever the new advisory level turns out to be, it will remain voluntary: agency officials have said they could take until 2021 to decide whether to attempt to set a legally enforceable maximum for PFOA.6

Table 1. Comparison of various PFOA levels with the safe level suggested by new research.

| Level of PFOA (parts per billion) |

Level of PFOA compared to safe level in new research |

|

|---|---|---|

| EPA Provisional (temporary) Health Advisory (2009) | 0.4 ppb | 1,333X |

| EPA Draft of Chronic (long-term) Health Advisory (2014) | 0.1 ppb | 333X |

| “Trigger level” for filtration of mid-Ohio Valley water systems covered by 2006 settlement | 0.05 ppb | 166X |

| Threshold for drinking water consumption by plaintiffs in upcoming personal injury trials | 0.05 ppb | 166x |

| PFOA level in Parkersburg, W.Va. water (2014) | 0.0412 ppb | 137X |

| PFOA level in Vienna, W.Va. water (2007) | 0.056 ppb | 187X |

| Lowest average level of detection of PFOA in state water systems, 2013-2015 (Va.) |

0.0109 ppb | 5x |

| Highest average level of detection of PFOA in state water systems, 2013-2015 (W.Va. ) |

0.0383 ppb | 174X |

Sources: EWG, from Grandjean and Clapp 2015; EPA 2009, 2015; Bilott to EPA 2015.

PFOA pollution is worldwide – and in people’s blood

Through Teflon’s use in hundreds of household products – carpets, clothing, food wrappers and many more – PFOA and closely related chemicals have spread to the remote corners of Earth, contaminating the blood of virtually all Americans and even passing through the umbilical cord to unborn babies in the womb.

PFOA has been linked to kidney and testicular cancers, birth defects, damage to the immune system, heart and thyroid disease, complications during pregnancy and other serious illnesses and conditions. It is hazardous at tiny doses: EPA’s health advisory level for drinking water is 0.4 parts per billion. (A part per billion, or ppb, is less than a teaspoon in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.)

Last June, the scientific journal New Solutions published a paper by Philippe Grandjean of the Harvard School of Public Health and Richard Clapp of the University of Massachusetts-Lowell, reviewing the research EPA used to set its health advisory level and comparing it to more recent studies.7

In setting its advisory level, EPA relied on studies before 2008 on the effects of PFOA and the closely related compound PFOS8, formerly used in 3M’s Scotchgard, on the weight of the liver and kidneys of rats and mice. PFOA toxicity testing has often been done using rats but female rats eliminate PFOA from their bodies much faster than people, so rats are not an ideal species for studying human developmental effects.9 EPA also considered PFOA only "suggestive" of carcinogenicity, but both an external review panel appointed by the agency and a science panel funded by the DuPont settlement10 later declared that PFOA is a “likely” cause of cancer.

Grandjean and Clapp cited a newer study by the National Toxicology Program, EPA and the University of North Carolina. This research concluded that PFOA could disrupt hormones and suggested a possible link to breast cancer.11 That study dosed mice in the womb with very low levels of PFOA during critical development periods and could not find a level so low it did not cause harm. The scientists also drew on Grandjean’s 2013 study of more than 400 children in the Faeroe Islands of the North Atlantic. These children’s diet was heavy in PFOA-contaminated fish. The results suggested that PFOA exposure could reduce the effectiveness of childhood vaccines.12

In another sign of the growing scientific recognition that PFOA is more harmful than previously thought, the National Toxicology Program recently announced a systematic re-evaluation of the chemical’s effect on the immune system. The program’s Office of Health Assessment and Translation issued a call for the submission of ongoing or upcoming studies to be considered in the evaluation and for the nomination of scientists for an expert panel to review the findings.

Grandjean and Clapp suggested that the EPA’s approach in 2009 led to a presumed safe level “at least two orders of magnitude” higher than the newer studies indicate would protect human health with an adequate margin of safety. Grandjean and Clapp termed 0.001 ppb the “approximate” safe level for PFOA, but EWG’s calculations from their data yielded a level of 0.0003 ppb – lower than the EPA advisory level by a factor of more than 1,300.

Phased out, but still a threat

Both PFOA and PFOS belong to a class of non-stick, waterproof, grease-proof chemicals historically called PFCs.13 Under pressure from EPA, 3M stopped making PFOS in 2002, and in 2005 DuPont agreed to phase out PFOA by this year. Those two chemicals are no longer produced in the U.S.

But DuPont and other chemical companies are marketing a new generation of PFCs with similar chemical structures. The few studies conducted on these new chemicals show that they may also have serious health risks. But the weak and outdated federal Toxic Substances Control Act has allowed them onto the market without adequate safety testing. Grandjean and Clapp wrote that “the greatly underestimated health risks from [PFOA] and [PFOS] illustrate the public health implications of assuming the safety of incompletely tested industrial chemicals.”

The new science demands urgent action to set stricter and legally enforceable limits on PFOA in drinking water. The threat to public health is most severe in the mid-Ohio Valley and the state-level test results reveal a problem nationwide. But federal regulators are moving at a glacial pace.

EPA was first alerted to PFOA pollution in the mid-Ohio Valley in 2001. Not until 2009 did it produce the current advisory level, which it called a “reasonable, health-based hazard concentration above which action should be taken to reduce exposure.”14 Last year, EPA released a draft15 of its proposed “reference dose” – an estimate of how much a person can safely consume daily over a lifetime. That proposed reference dose would translate to a legal limit for PFOA of 0.1 ppb.

That’s a quarter of the current advisory level but still more than 300 times the safe level put forth by Grandjean and Clapp. What’s more, the EPA draft study says that PFOA exposure is only “suggestive of carcinogenicity,” again disregarding the findings in 2006 of EPA’s own Science Advisory Panel that PFOA is a “likely” human carcinogen.

EPA’s draft study and the findings of the nationwide water sampling will drive the decision of whether to set a legal limit for PFOA in drinking water, and it is far from certain that the agency will act. In February of last year, Nancy Stoner, EPA’s acting water chief, told Inside EPA: “The agency expects that we will have sufficient information to determine whether it is appropriate to develop a drinking water regulation for PFOA within the next 5 to 7 years.”16

In other words, EPA officials think they need as much as seven years to decide whether to even propose a legal limit for PFOA. If they do make a proposal, the rule-making process is so protracted that many more years could elapse without a legal maximum for a compound whose threat to health at low doses has been confirmed by scores of peer-reviewed studies.

Nationwide water sampling

Nationwide sampling for PFOA, PFOS and four other PFCs17 in drinking water began in 2013, under an EPA program18 that periodically requires all U.S. public water systems serving 10,000 or more people to test for contaminants that are not yet regulated. Through July of this year, the current round of the program had tested more than 29,000 samples. Fewer than one percent of the samples had detectable levels of PFOA. But critics, including the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and the American Water Works Association, said in comments to EPA that the tests were not designed to detect very low levels of the chemicals.19

In 2006 New Jersey conducted its own tests for PFOA and other PFCs in drinking water. The methods used by New Jersey officials were approximately 10 times the sensitivity of those specified by EPA. The less sensitive EPA tests and reporting threshold used for the nationwide sampling program would have missed almost three-fourths of the PFC water contamination New Jersey officials found in their state. New Jersey’s testing prompted state regulators to set their own non-enforceable health advisory level for PFOA in drinking water of 0.04 ppb – ten times more protective than EPA’s advisory level, but still more than 130 times the amount Grandjean and Clapp said is safe.

The results of the nationwide tests could mean that EPA will decline to propose an enforceable rule for PFOA in drinking water, because the federal Safe Drinking Water Act requires that when the agency decides whether to issue a rule with the force of law, it must consider “the frequency and level of contaminant occurrence in public drinking water systems.”20 Yet the new research shows that the average of levels detected in each state are between five and 175 times too high to be considered safe.

The EPA-mandated tests by local water systems found PFOA in 27 states, in 94 water systems serving 6.5 million Americans. The results show that outside of the mid-Ohio Valley, New Jersey and California have the most widespread PFOA contamination. Testing in both states found PFOA in 14 water systems, serving more than 1.4 million people in California and more than 1.3 million people in New Jersey. By the most conservative estimate, the average level of PFOA detected in California samples was 14 times the level Grandjean and Clapp say is safe, and in New Jersey it was 30 times the new safe level.

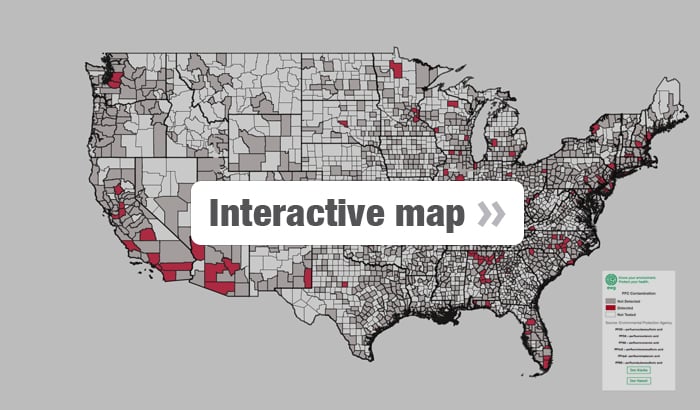

The table below shows average levels of PFOA in water samples, and by how much they exceed the new safe level according to Grandjean and Clapp. EWG has also produced an interactive map that shows nationwide detections of PFOA, PFOS and four other PFCs.

Table 2. Nationwide sampling found that statewide average detections of PFOA in drinking water greatly exceed the safe level established by the new research.

| State | Number of systems with water samples with PFOA | Number of water samples with PFOA | Percent of samples with PFOA detected | Population served by drinking water systems with PFOAa | Range of average level of PFOA in samples (parts per billion)b | Average level of PFOA compared to safe level in new research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 12 | 26 | 25% | 312,522 | 0.0081-0.0231 | 27-77X |

| Arizona | 4 | 14 | 15% | 217,218 | 0.006-0.0219 | 20-73X |

| California | 14 | 39 | 14% | 1,441,298 | 0.0041-0.035 | 14-117X |

| Colorado | 3 | 52 | 78% | 57,343 | 0.0361-0.0397 | 120-132X |

| Delaware | 2 | 12 | 30% | 320,494 | 0.0172-0.0269 | 57-90X |

| Florida | 2 | 4 | 7% | 371,913 | 0.0028-0.017 | 9-57X |

| Georgia | 2 | 3 | 100% | 94,674 | 0.0367 | 122X |

| Illinois | 3 | 3 | 33% | 135,753 | 0.0136-0.0209 | 45-70X |

| Kentucky | 1 | 2 | 25% | 730,611 | 0.005-0.0131 | 17-44X |

| Massachusetts | 3 | 7 | 21% | 103,762 | 0.0062-0.0168 | 21-56X |

| Maryland | 1 | 1 | 10% | 104,567 | 0.0021-0.012 | 7-40X |

| Minnesota | 4 | 6 | 26% | 143,637 | 0.0256-0.0346 | 85-115X |

| North Carolina | 5 | 8 | 9% | 225,262 | 0.002-0.0192 | 7-64X |

| New Hampshire | 2 | 2 | 17% | 53,000 | 0.0091-0.0184 | 30-61X |

| New Jersey | 14 | 60 | 33% | 1,334,413 | 0.0091-0.0272 | 30-91X |

| New York | 3 | 4 | 8% | 174,000 | 0.0028-0.0163 | 9-54X |

| Ohio | 3 | 3 | 33% | 79,337 | 0.008-0.0153 | 27-51X |

| Oklahoma | 1 | 1 | 33% | 20,307 | 0.0113-0.0182 | 38-61X |

| Pennsylvania | 5 | 24 | 25% | 221,121 | 0.0193-0.0337 | 64-112X |

| Rhode Island | 1 | 1 | 25% | 21,900 | 0.0203-0.0281 | 68-94X |

| South Carolina | 1 | 1 | 25% | 24,904 | 0.006-0.0138 | 20-46X |

| Tennessee | 1 | 1 | 25% | 139,110 | 0.005-0.0128 | 17-43X |

| Texas | 1 | 1 | 25% | 11,489 | 0.0066-0.0144 | 22-48X |

| Virginia | 1 | 1 | 7% | 47,574 | 0.0016-0.0122 | 5-41X |

| Washington | 3 | 6 | 23% | 109,527 | 0.0067-0.0163 | 22-54X |

| Wisconsin | 1 | 3 | 21% | 30,100 | 0.0063-0.0153 | 21-51X |

| West Virginia | 1 | 2 | 100% | 34,251 | 0.0522 | 174X |

| Total | 94 | 287 | 23% | 6,560,087 |

Sources: EWG, from Grandjean and Clapp 2015; EPA 2009, 2015; Bilott to EPA 2015.

a From the EPA Safe Drinking Water Information System 2013 Inventory.

b EPA only required reporting of PFOA levels above 0.02 ppb, even if the laboratories testing the samples had lower limits of detection. The average PFOA values for each state are provided as a range, calculated using zero and 0.02 ppb as the value for all non-detects.

PFOA found in 94 public water systems in 27 states

| State | County | Public Water System | Population served |

| Alabama | Chilton | Clanton Water Department | 13,500 |

| Colbert | Colbert County Rural Water System | 10,731 | |

| Cullman | VAW Water System, Inc. | 14,958 | |

| DeKalb | Northeast Alabama Water System | 37,500 | |

| Etowah | Gadsden Waterworks & Sewer Board | 46,551 | |

| Rainbow City Utilities Board | 11,748 | ||

| Southside Waterworks | 10,800 | ||

| Lauderdale | Florence Water-Wastewater Department | 66,900 | |

| Lawrence | West Lawrence Water Co-op | 14,517 | |

| Marshall | Albertville Utilities Board | 29,991 | |

| Boaz Water & Sewer Board | 29,196 | ||

| Morgan | West Morgan - East Lawrence Water Authority | 26,130 | |

| Arizona | Gila | Town of Payson | 17,682 |

| Maricopa | Liberty Water LPSCO | 34,000 | |

| City of Tempe | 165,000 | ||

| Mohave | Oatman Water Company | 536 | |

| California | Los Angeles | Santa Clarita Water Division | 111,000 |

| City of Pico Rivera Water Department | 39,000 | ||

| Orchard Dale Water District | 22,492 | ||

| Valencia Water Company | 116,361 | ||

| Orange | City of Orange | 138,640 | |

| Yorba Linda Water District | 77,513 | ||

| Riverside | Eastern Municipal Water District | 503,700 | |

| Elsinore Valley Municipal Water District | 133,786 | ||

| City of Norco | 27,160 | ||

| City of Corona | 155,896 | ||

| Sacramento | CA American Water Co. - Suburban | 33,914 | |

| San Diego | Camp Pendleton (South) | 39,400 | |

| San Joaquin | City of Lathrop | 12,427 | |

| San Luis Obispo | Atascadero Mutual Water Company | 30,009 | |

| Colorado | El Paso | City of Fountain | 20,000 |

| Security WSD | 19,000 | ||

| Widefield WSD | 18,343 | ||

| Delaware | New Castle | Artesian Water Company | 211,494 |

| United Water Delaware | 109,000 | ||

| Florida | Broward | City of Miramar | 122,041 |

| Escambia | Emerald Coast Utilities Authority | 249,872 | |

| Georgia | Floyd | Rome | 45,586 |

| Gordon | Calhoun | 49,088 | |

| Illinois | Knox | Galesburg | 31,700 |

| McLean | Bloomington | 77,610 | |

| Stephenson | Freeport | 26,443 | |

| Kentucky | Jefferson | Louisville Water Company | 730,611 |

| Maryland | Harford | Harford County DPW | 104,567 |

| Massachusetts | Barnstable | Hyannis Water System | 35,000 |

| Essex | Danvers Water Department | 26,762 | |

| Hampden | Westfield Water Department | 42,000 | |

| Minnesota | Dakota | Hastings | 22,652 |

| Washington | Cottage Grove | 30,820 | |

| Oakdale | 27,378 | ||

| Woodbury | 62,787 | ||

| New Hampshire | Hillsborough | Merrimack Village District | 25,000 |

| Strafford | Dover Water Department | 28,000 | |

| New Jersey | Atlantic | Atlantic City MUA | 150,000 |

| Bergen | Fair Lawn Water Department | 32,573 | |

| Garfield Water Department | 29,786 | ||

| Ridgewood Water | 61,700 | ||

| Wallington Water Department | 12,000 | ||

| Hawthorne Water Department | 21,006 | ||

| Camden | Aqua NJ - Blackwood | 49,190 | |

| Essex | Montclair Water Bureau | 38,977 | |

| Orange Water Department | 33,000 | ||

| Middlesex Water Company | 233,376 | ||

| Ocean | Lakewood Township MUA | 17,400 | |

| Point Pleasant Water Department | 19,600 | ||

| Union | NJ American Water Co. - Raritan | 609,305 | |

| United Water - Rahway | 26,500 | ||

| New York | Jefferson | Fort Drum | 34,000 |

| Nassau | Town of Hempstead Water District | 110,000 | |

| New Windsor Consolidated Water District | 30,000 | ||

| North Carolina | Brunswick | Brookwood Comm. Water System | 15,665 |

| Harnett | Harnett County Department of Public Utilities | 90,004 | |

| Moore | Moore County Public Utilities - Pinehurst | 19,368 | |

| Orange | Orange Water & Sewer Authority | 80,000 | |

| Town of Fuquay-Varina | 20,225 | ||

| Ohio | Gallia | Gallia County Rural Water Association | 20,546 |

| Greene | Wright-Patterson AFB Area A/C | 11,791 | |

| Mahoning | Aqua OH - Struthers | 47,000 | |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma | Bethany | 20,307 |

| Pennsylvania | Bucks | Aqua PA - Bristol | 35,343 |

| Warminster Municipal Authority | 40,000 | ||

| Warrington Township Water & Sewer Department | 15,129 | ||

| Dauphin | United Water PA | 105,649 | |

| Horsham Water & Sewer Authority | 25,000 | ||

| Rhode Island | Providence | Town of Cumberland | 21,900 |

| South Carolina | Spartanburg | Woodruff Roebuck Water District | 24,904 |

| Tennessee | Rutherford | Consolidated Utility District of Rutherford | 139,110 |

| Texas | Calhoun | City of Port Lavaca | 11,489 |

| Virginia | Washington | Washington County Service Authority | 47,574 |

| Washington | King | Issaquah Water System | 22,926 |

| Pierce | City of Dupont Water System | 12,042 | |

| Fort Lewis Water - Cantonment | 74,559 | ||

| Wisconsin | Washington | West Bend Waterworks | 30,100 |

| West Virginia | Wood | Parkersburg Utility Board | 34,251 |