When it’s confronted with the growing concern about the vast volumes of water used in hydraulic fracturing of gas and oil wells, industry tries to dodge the question.

The American Petroleum Institute (API) points out that drilling wells with hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling technology, commonly called “fracking,” consumes far less water than other commonplace activities such as raising livestock, irrigating crops or even watering golf courses. According to the Institute, the amount of water used to frack one natural gas well “typically is the equivalent of three to six Olympic swimming pools.”1

That amounts to 2-to-4 million gallons per well of a precious and, in many parts of the country, increasingly scarce resource.2 For its part, the Environmental Protection Agency says it takes “fifty thousand to 350,000 gallons to frack one well in a coal bed formation, while two-to-five million gallons of water may be necessary to fracture one horizontal well in a shale formation.”3

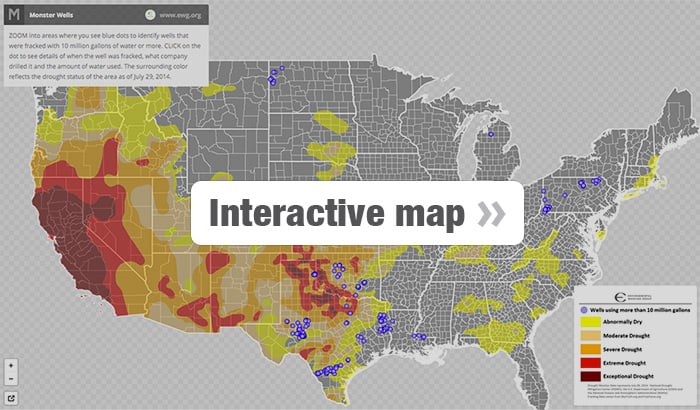

But data reported and verified by the industry itself reveal that those “typical” amounts are hardly the upper limit. An analysis by Environmental Working Group reveals that hundreds of fracked gas and oil wells across the country are monster wells that required 10 million to almost 25 million gallons of water each.

Between April 2010 and December 2013 (the latest figures available), data from the industry-operated website FracFocus.org, acquired by Skytruth.org, show that there were 261 wells fracked with at least 10 million gallons of water each (Table 1). EWG’s analysis found:

- It took a grand total of more than 3.3 billion gallons of water to frack the 261 wells – an average of 12.7 million gallons each. Fourteen used more than 20 million gallons each.

- About two-thirds of the wells, requiring a total of about 2.1 billion gallons, were in drought-stricken areas.

It’s far more relevant to compare those figures to basic human needs for water, rather than to swimming pools or golf courses. The 3.3 billion gallons consumed by the monster wells was almost twice as much water as is needed each year by the people of Atascosa County, Texas, in the heart of the Eagle Ford shale formation, one of the most intensively drilled gas and oil fields in the country.4 Like almost all of the Lone Star State, Atascosa County, south of San Antonio, is in a severe and prolonged drought. Last year, the state water agency cited oil and gas exploration and production as a factor in the dramatic drop of groundwater levels in the aquifer underlying the Eagle Ford formation. 5

Drilling Through Drought

Fracking fluid used by gas and oil drilling companies is a mixture of water, chemicals and sand, which is injected into rock formations deep underground to open up hard-to-reach oil and gas deposits. Fracking fluids typically are more than 95 percent water.

Most of that is fresh water from surface or ground water sources, although brackish water, treated wastewater and recycled fracking water previously are also used in some areas. Some companies have also used alternative fluids such as liquid propane or butane, but these alternatives are rare.

EWG matched data from FracFocus with the drought status of all 261 monster well locations at the time each one was drilled, as tracked by the U.S. Drought Monitor,6 a project of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska.

The data show that about two-thirds were drilled in areas beset by drought or abnormally dry conditions and used more than 2.1 billion gallons of water. About one-third were located in areas of severe, extreme or exceptional drought.

The impact on water supplies does not end once the well is fracked. If 10 million gallons of water are injected into a well, millions of gallons of contaminated water come back up. It has to go somewhere.

According to the EPA, 10- to-70 percent percent of the water used for fracking returns to the surface,7 and it can contain high levels of salts, metals, radioactive contaminants and toxic chemicals. It generally cannot be reused without treatment. Because of the high costs and technological challenges of treating this water, most of it is instead re-injected into deep underground wells for permanent disposal.8 But it often doesn’t stay there.

In 2012, an investigation by journalists at the non-profit ProPublica found that disposal wells “have repeatedly leaked, sending dangerous chemicals and waste gurgling to the surface or, on occasion, seeping into shallow aquifers that store a significant portion of the nation’s drinking water.” ProPublica quoted a former EPA expert on underground disposal wells who said: “In 10 to 100 years we are going to find out that most of our groundwater is polluted.” 9

In August of this year, Stanford University researchers reported that in Wyoming, drillers are fracking at “far shallower depths than widely believed, sometimes through underground sources of drinking water,”10 increasing the risk of contaminating water supplies with fracking fluids.

Texas Town Went Dry

When contacted by EWG, several companies responsible for drilling monster wells took pains to point out that the water they used was either recycled from other frack jobs or brackish water unsuitable for other purposes. But in the states with the most monster wells – Texas, Pennsylvania and Colorado – the vast amount of water being used for fracking, and disposed of after fracking, is clearly having an impact on water supplies.

- In Irion County, Texas, which has the most monster wells of any county in the nation, the town of Barnhart’s municipal water supply ran dry in August 2013 after hundreds of water wells were drilled to supply fracking operations. In adjacent Crockett County, local officials say fracking accounts for up to 25 percent of all water use.11

- In April 2012, the Susquehanna River Basin Commission temporarily suspended 17 water withdrawal permits in Pennsylvania, the majority of them related to natural gas development, to protect the aquatic environment and downstream users.12

- In Colorado, oil and gas drillers are outbidding farmers at water auctions, paying more than 10 times as much per acre-foot as growers are accustomed to paying.13 One farmer in drought-stricken eastern Colorado said, “It’s not a level playing field. I don’t think the farmer can compete with the oil and gas companies for that water.”14

Industry Website Is Flawed and Incomplete

FracFocus went online in April 2011 as an industry-maintained database where drillers could report the chemicals used to frack each well and the amount of water they used. It is funded in part by America’s Natural Gas Alliance and the American Petroleum Institute, and the data have repeatedly been shown to be substantially incomplete.15,16

Fracking is known to be used in 36 states, but only 15 require reporting to FracFocus; in other states it is voluntary.17 None of the numbers are verified by a regulatory agency or other independent authority, and key data for individual wells is often missing. For example, for 38 of the 261 monster wells EWG identified, Frac Focus does not even say whether they were drilled for oil or gas. Nor does FracFocus report whether a well was fracked with fresh, recycled or brackish water.

FracFocus is not managed or overseen by a public regulatory agency responsible for ensuring compliance with state and federal laws, does not present data in an easily searchable format and does not allow for aggregation of data across well sites or states. A Bloomberg investigation found that more than half of the wells fracked in the last 10 months of 2011 in Texas, Oklahoma and Montana were not listed on FracFocus, and that more than 90 percent of the companies that drilled new wells in that period didn’t report any of them on FracFocus.18

Although the monster wells EWG identified on FracFocus are a small fraction of the total number of wells fracked in that period, it is likely that there are an unknown number of other, unreported monster wells across the country – and given the breakneck expansion of fracking, more to come. What’s more, many wells are fracked more than once – what the industry calls multi-stage fracking – so the 2011-2013 FracFocus data may not reflect the total volume of water that will ultimately be used to frack a particular well.

In July 2014, EWG attempted to verify the data on the 261 monster wells by contacting the listed well operators by email and, if there was no response, by a follow-up phone call. EWG eventually received responses for 99 wells. All those who responded verified the amount listed in FracFocus except for two wells. For one, the drilling company corrected the reported amount of water used from 17.9 million gallons to 13.9 million gallons, which still left it ranked number 59 on the monster well list. For the other, the company said the amount reported to FracFocus – more than 11.7 million gallons – was incorrect, but it could not supply the correct amount. As of August 2014, the number reported on FracFocus has not changed.

The Biggest Monster Wells (Table-1)

Table 1. In 2011-13, 14 monster wells used at least 20 million gallons of water each

| State | County | Type | Name | Date19 | Company | Gallons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEXAS | Harrison | N/A | Swepco Deep #1H | 3/22/13 | Sabine Oil & Gas LLC | 24.8 million |

| COLORADO | Garfield | Gas | Federal 36-1H (ON1) | 10/10/11 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 24.0 million |

| COLORADO | Mesa | Gas | Orchard Unit 30-5H (K20OU) | 12/8/11 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 22.8 million |

| COLORADO | Mesa | Gas | Keinath Federal 10-10H (C16OI)) | 4/4/11 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 22.6 million |

| NORTH DAKOTA | William | Oil | Strid 2-26H | 2/5/13 | Continental Resources Inc. | 22.1 million |

| TEXAS | Panola | Gas | Liston 8H | 12/6/12 | XTO Energy Inc. | 21.8 million |

| COLORADO | Mesa | Gas | Keinath Federal 17-11AH (C16OU) | 3/8/11 | Encanca Oil & Gas (USA) Inc | 21.5 million |

| MICHIGAN | Kalkaska | Gas | State Excelsior 325 HD-1 | 10/30/12 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 21.1 million |

| COLORADO | Garfield | Gas | DW 8608E-28 P28 496 | 1/6/13 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 21.1 million |

| TEXAS | Panola | Gas | Walton 10H | 10/26/12 | XTO Energy Inc. | 20.7 million |

| COLORADO | Garfield | Gas | Benzel 35-2HM (F25NWB) | 11/11/11 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 20.6 million |

| LOUISIANA | St. Helena | N/A | Weyerhaeuser 60H-01 | 1/23/13 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 20.4 million |

| COLORADO | Mesa | Gas | Stewart 36-13H (PL36SW) | 6/25/11 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 20.3 million |

| COLORADO | Mesa | Gas | Keinath Federal 17-11H (C16OU) | 3/8/11 | Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. | 20.1 million |

| TOTAL | 304.1 million |

Source: Environmental Working Group analysis of data from FracFocus.org

Where Monster Wells Were Drilled

Texas

Texas has had by far the most of any state. Its 149 monster wells used a total of more than 1.85 billion gallons – well over half of the total number of wells and volume of water. Texas’ monster wells used an average of more than 12.4 million gallons each

On the full list of 261 wells, the largest water user was one in Harrison County, Texas, drilled in March 2013 by Sabine Oil & Gas LLC, which used more than 24.8 million gallons. The company did not report to FracFocus whether it was for oil or natural gas. The Texas county that was home to the most monster wells was Irion, with 19 wells that used an average of 12.9 million gallons of water each.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania had 39 monster wells, which used a total of more than 384 million gallons of water. They used an average of more than 11.3 million gallons each.

The largest water user in Pennsylvania was a natural gas well in Tioga County, drilled in February 2012 by Seneca Resources Corp., which used more than 18.7 million gallons. It ranked 17th on the national list of monster wells. The county with the most monster wells was Greene, with18 wells using an average of 11.2 million gallons each.

Colorado

Colorado had 30 monster wells, which used a total of almost 470 million gallons. They used an average of more than 15.6 million gallons of water each.

The largest water user in Colorado was a natural gas well in Garfield County, drilled in October 2011 by Encana Oil & Gas, which used more than 24 million gallons, enough to rank second on the national list.The Colorado county with the most monster wells was Garfield, with 16 wells using an average of 14.7 million gallons each.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma had 24 monster wells, which used a total of about 302 million gallons of water. They used an average of more than 12.6 million gallons each.

The largest water user in Oklahoma was in Pittsburg County, drilled in February 2012 by Newfield Exploration. It used more than 16.4 million gallons, which ranked 28th nationally. The company did not report the type of well to FracFocus. The Oklahoma county with the most monster wells was Pittsburg, with seven wells using an average of almost 13.3 million gallons each.

North Dakota

North Dakota had 11 monster wells, which used a total of almost 129 million gallons of water, for an average of more than 11.7 million gallons per well.

The largest water user in North Dakota was an oil well in Williams County, drilled in February 2013 by Continental Resources, which used more than 22.1 million gallons, ranking fifth nationally. All but three of the 11 monster wells in North Dakota were in McKenzie County, averaging 10.6 million gallons per well.

Louisiana

Louisiana had three monster wells, which used a total of about 42 million gallons of water for an average of about 14 million gallons each.

The largest water user in Louisiana was in St. Helena County, drilled in January 2013 by Encana Oil & Gas, which used more than 20 million gallons. It ranked 12th on the national list. The company did not report the type of well to FracFocus.

Mississippi

Mississippi also had three monster wells, which used a total of more than 38.4 million gallons of water, for an average of about 12.8 million gallons apiece. The largest water user in Mississippi was an oil well in Wilkinson County, drilled in January 2013 by Goodrich Petroleum Co., which used 13.7 million gallons, ranking 64th nationally.

Michigan

Michigan had two monster wells, which together used more than 33.6 million gallons of water. The largest was an oil well in Kalkaska County, drilled in October 2012 by Encana Oil & Gas, which used more than 21 million gallons, ranking eighth nationally.

Six Companies Drilled Monster Wells (Table-2)

Table 2. Companies drilling the most monster wells, Jan. 2011 – May 2013

| Company | Wells | Gallons | Average |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Encana Oil & Gas (USA) Inc. |

35 | 545.6 million | 15.6 million |

|

EOG Resources, Inc. |

39 | 476.9 million | 12.2 million |

|

Newfield Exploration |

26 | 342.3 million | 13.2 million |

|

EQT Production |

20 | 231.7 million | 11.6 million |

|

Devon Energy Production Co. |

16 | 182.8 million | 11.4 million |

|

Murphy Exploration & Production USA |

16 | 177.8 million | 11.1 million |

Source: Environmental Working Group analysis of data from FracFocus.org

The company that used the most water to frack its monster wells during the period analyzed was a Canadian firm, Encana Corp. of Calgary, Alberta. Its U.S. subsidiary, Encanca Oil & Gas (USA) Inc., fracked 35 monster wells in Colorado, Texas, Louisiana, Michigan and Mississippi. The largest user of water was a gas well in Garfield County, Colo., that used more than 24 million gallons.

On its website, Encana is transparent about its water use, although it expresses the volume in less familiar units that appear to minimize the numbers. Encana says it “may use anywhere between 200 and 120,000 cubic metres” of water to frack a well. That is about 52,000 to 31.7 million gallons – a top figure considerably higher than the thirstiest well the company reported to FracFocus during the period analyzed.20

The company that fracked the most monster wells was EOG Resources, Inc., based in Houston. It fracked 39 of them, all in Texas except one in Louisiana. The largest water user was an oil well in Irion County, Texas, that used more than 17 million gallons.

EOG’s website does not say how much water it uses for fracking. Instead, it resorts to the common industry practice of comparing fracking water use to other uses:

Hydraulic fracturing accounts for only about 0.5 percent of all the water used across Texas. . . Irrigation is the biggest user of water in Texas, accounting for 61 percent. Municipal use follows with 27 percent, then manufacturing at 6 percent, steam electric power at 3 percent and livestock at 2 percent. . . . Lawns [in Texas] consume roughly 18 times more water than fracking does.21

EOG also touts its low rate of water intensity, the amount needed to produce a unit of energy: “EOG’s water intensity rate for 2013 (that is, the water used by EOG in completing its U.S. wells in 2013 relative to the potential [energy] value of the oil and gas reserves associated with such wells) was 1.83 gallon per MMBtu [1 million British Thermal Units].” According to EOG, that is less water than is needed to produce the same amount of energy from coal, nuclear power, synthetic fuels, corn ethanol and soy biodiesel.22

The other companies with the most monster wells were even less forthcoming on their websites:

- Newfield Exploration Co. says only: “Our environmental stewardship relates to Newfield’s impacts on living and non-living natural systems, including ecosystems, land, air and water.”23

- EQT Production says that in 2012 it used a total of about 2.3 million cubic meters (605 million gallons) of fresh water for fracking, and that almost a third of the total was recycled and reused. But there is no discussion of the amount used per well.24

- Devon Energy touts its water reuse program in Oklahoma, which it says has saved 80 million gallons of water since 2013, but it provides no information about how much water it uses.25

- Murphy Exploration says only that it is committed to “reducing emissions, increasing energy efficiencies, protecting water resources, and managing waste and land impact.”26

Monster Wells Are Common in Drought Areas (Table-3 & Table-4)

By a wide margin, Texas had the most monster wells drilled in abnormally dry or drought areas, as classified by the U.S. Drought Monitor, with 137 in the period examined. Of the other states, only Colorado had as many as 11 wells in abnormally dry or drought areas.

Table 3. Texas Monster Wells in Drought Areas, Jan. 2011 – May 2013

| Drought condition | Monster wells |

|---|---|

| Abnormally dry | 29 |

| Moderate | 49 |

| Severe | 33 |

| Extreme | 18 |

| Exceptional | 8 |

Source: Environmental Working Group analysis of data from FracFocus.org and the U.S. Drought Monitor

Texas not only has the most monster wells and the most monster wells in drought areas but uses more fresh water for fracking. The industry says the geology of the state’s production regions makes using fresh, pure water more effective – and cheaper.

In the Permian Midland oil field, “some operators purchase water from landowners or even cities and truck it in,” reported the San Angelo Standard-Times, “but most forgo the added expense and drill water wells on site, store the water in pits temporarily and then haul it in trucks to oil well sites.”27

A report from the University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology, prepared for the Texas Oil & Gas Association, estimates that statewide 79 percent of the water used for fracking is fresh. In 2011, more than 21 billion gallons of fresh water were used for fracking in Texas.28, 29

Table 4. Types of Water for Fracking in Texas Oil and Gas Producing Regions, 2011

| Region | Recycled | Brackish | Fresh |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anadarko Basin | 20% | 30% | 50% |

| Barnett | 5% | 3% | 92% |

| Eagle Ford | 0 | 20% | 80% |

| East Texas Basin | 5% | 0 | 95% |

| Permian Far West | 0 | 80 | 20% |

| Permian Midland | 2% | 30% | 68% |

Source: Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas at Austin School of Geosciences, 2012

Conclusion and Recommendations

The oil and gas industry maintains that the amount of water used in fracking is insignificant compared to other uses and that the fracking boom poses no threat to water quantity or quality But that argument doesn’t stand up to the facts, based on the industry’s own websites and the data that drillers report to FracFocus. There is a good reason the industry downplays and obscures the truth about the huge volumes of water used in fracking: The real story is alarming – especially in parts of the country suffering from drought, a condition that is becoming more common with global warming. Though the monster wells EWG found in FracFocus are only a fraction of the thousands of wells drilled in the United States every year, but they point to a serious situation that will only become more acute as fracking spreads and water supplies grow scarcer.

The industry likes to argue that fracking for oil and gas is meeting an important public need – producing energy. That may be true, but it has also produced huge profits, and with the current U.S. glut of oil and gas, an increasing amount of the energy produced is being exported to other countries.30, 31 It is unreasonable for private companies to profit from the use of a finite public resource while cities, communities and farms may be forced to cut back when supplies run low. In Texas, where the fracking boom coincides most directly with water shortages, some counties do not even require companies to obtain permits to drill wells that may be fracked with 10 million or more gallons of water. 32

That must change. What must also change is the unreliable, error-prone, industry-controlled system of tracking the vast amounts of water used for tracking. EWG recommends:

- State or local authorities should require oil and gas companies to obtain water use permits for every well they drill. Applications for permits should disclose not only the amount of water used but its source and type and how it will be recycled or disposed of.

- State and local authorities should be able to deny or limit permits for wells they judge to require an excessive amount of water.

- In times of officially declared drought, oil and gas drilling operations should be subject to the same kind of water use restrictions imposed on citizens, farmers, communities, recreational activities and other industries. Ensuring access to clean, safe affordable drinking water should always be the top priority.

- To improve reporting and tracking of water use, FracFocus must be replaced with an independent database, overseen by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, modeled on the Toxics Release Inventory. This database should require disclosure of the amount of water used; its source; whether it was fresh, recycled or brackish; and how it was recycled or disposed of.