With deliberations on the 2012 farm bill due to begin in January, EWG looks at how the industrial agriculture lobby dominates the hearing process, leaving little room for good food reformers.

Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) announced at the Farm Journal Forum today (Dec 6) that work on the 2012 farm bill will start in earnest in January. This is a different tack than she and the other Agriculture Committee leaders in Congress took just last month when it became clear that the current system of lavish and wasteful agricultural subsidies was at last headed for defeat. It was at that point that the die-hard defenders of the status quo who lead the House and Senate Ag Committees had a brainstorm. They set out to write a bill that would protect the giveaways that mostly enrich already profitable mega-farms and pushed to incorporate their draft in the deficit-reduction bill of the now-failed Super Committee, where the bill could not have been amended or even openly discussed.

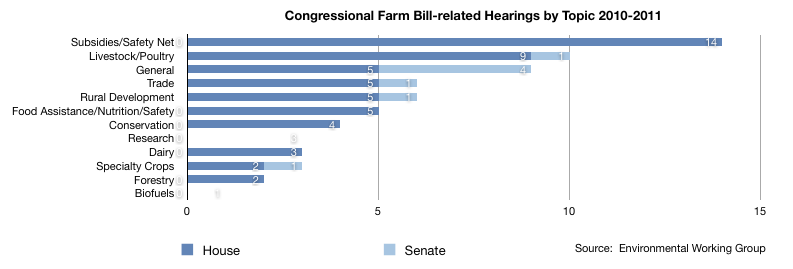

Their work was quickly branded the “secret farm bill.” That this label stung the Ag Committee leaders was evident in their strenuous attempt to push back. They said they had held numerous hearings – anywhere from 14 to 23 – on the farm bill and related issues. (Strangely, they didn’t give themselves enough credit. By our count, between early 2010, when the current farm bill programs took full effect, and August of this year there were as many as 66 hearings on those issues.)

But counting hearings to assess whether Congress did its due diligence prior to writing the secret farm bill is largely a red herring. Congress is, after all, paid to do just that.

Senator Stabenow also indicated at the Farm Journal Forum that the secret farm bill work would be the foundation for the 2012 farm bill. As we enter 2012 and the process returns to the “usual order” of reauthorizing the Farm Bill every five years, the question is not how many hearings are held – but who gets to testify and what information is collected. None of the hearings cited by committee leaders tried to really address our badly broken food and farm system, a discussion that the taxpayers who bankroll the system deserve to hear. What they got instead were recycled industrial agriculture talking points and padding from Ag Committee press releases

The way things were going, Congress could have called 10,000 witnesses in 1,000 hearings and heard nothing but recycled calls for more commodity subsidies and less regulation. As for the 78 percent of Americans who say that making nutritious and healthy foods more affordable and more accessible should be a top priority in the next farm bill, they’d still go unheard.

So what was discussed in those 60 plus hearings on farm bill issues? Nearly one-fourth addressed the farm “safety net” – i.e., subsidies and taxpayer-subsidized insurance. Dairy, livestock, commodity crops and biofuels, industrial agriculture were the focus of more than half of the hearings. And every one of the “safety net” hearings were held in 2010 – an election year – and featured only testimony from witnesses invited by the committee members. That’s what you call a “cheerleading session.”

As you might imagine, none of those witnesses suggested cutting subsidies for industrial agriculture or addressed questions of need and balance in doling out taxpayers’ dollars. More than half the hearings addressed less than 15 percent of total farm bill spending. Nutrition, which accounts for almost 70 percent of that spending, was the subject of only five hearings – three of them focusing on food delivery problems on Indian reservations, one on food safety and one scrutinizing recipients of food assistance.

What hasn’t been discussed, not even once? The actual quality of the food supply and the “nutrition” Americans receive from it; or the detrimental consequences of industrial ag practices, such as soil erosion and water pollution from chemical fertilizers and pesticides. We hope that someone in Congress has looked into these issues, but if so, there is no public record of what information the members base their decisions on.

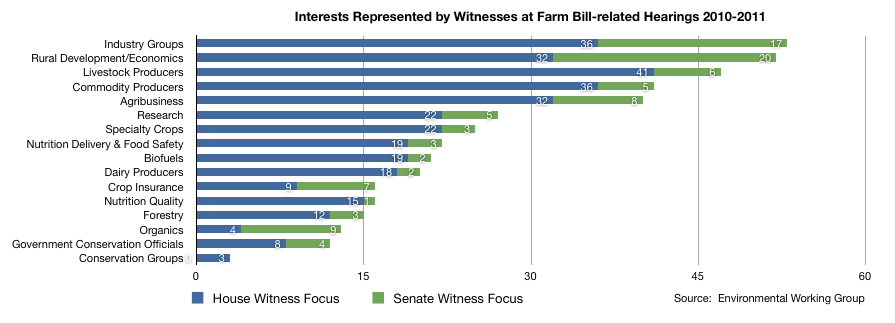

The record shows that those who were invited to testify or submitted written comments addressed about 250 separate “interests.” It’s an impressive-sounding number, but 165 of them represented commodities, agribusiness, biofuels or crop insurance and banking interests. Only 25 addressed “specialty crops” (that’s fruits and vegetables) in their testimony, only 16 were invited to discuss issues of nutritional quality, and only 13 spoke on organic farming. It is not difficult to see why the secret farm bill was poised to give commodity crops and insurance an entirely new and lavish subsidy even at a time of high farm income and tight federal budgets.

What about hearings on improving the quality of the food system? There were none. What about conservation programs, which represent nearly 10 percent of Farm Bill spending and provide billions in taxpayer benefits? In two years, only three non-government witnesses discussed them. . . and the secret farm bill targeted those programs for a devastating $6.5 billion in cuts.

This points to one simple fact: the more members of Congress actually learn about an issue, the more understanding they bring to the budget discussions, and when they listen mostly to just one set of interests, they make decisions that serve those interests.

Consumers and taxpayers have a right to have all aspects of the Farm Bill publicly discussed and considered. The voices that should be heard before the bill is written should include, among others, representatives of:

- farmers’ markets, which are enjoying robust growth and have nearly $5 billion in annual sales, who could address how taxpayer support could encourage healthier fresh food options at the local level;

- restaurants and food service providers engaged in “farm-to-table” programs, who could speak to the need for government support to improve food distribution systems;

- food banks and other assistance organizations, who could paint a picture of the food and nutrition needs of America’s neediest citizens;

- educators, who could detail the challenges faced in providing healthy lunches to America’s children;

- the health and nutrition sectors, who could explain the linkages between agricultural policies and America’s multiple health epidemics;

- rural and urban water systems, like the Ohio utility that faces extra costs of $3,000 to $4,000 a day to remove agricultural pollutants from Toledo’s water;

- local environmental groups, who could outline how they use taxpayer dollars to leverage private matching funds to boost conservation efforts and provide the greatest return on public investment; and

- government auditing agencies, who could look as carefully for fraud and waste in agricultural subsidies as Congress has done in scrutinizing food assistance programs and environmental regulation.

As Reps. Ron Kind (D-Wis.) and Jeff Flake (R-Ariz.) said in their invitation to a recent farm bill briefing for members of Congress:

Before deciding the fate of billions of dollars a year in farm subsidies, Congress has the obligation to understand the choices being made.

We couldn’t agree more. No matter how many hearings are held, no matter how many witnesses are paraded before the committees, and no matter how many closed-door meetings are held to write legislative language, the farm bill will still be a “secret” one unless Congress does due diligence on all aspects of the authorized spending, and unless taxpayers and consumers are allowed to see how their input is reflected in the final product.